Two nights ago, Talie, Shelly, and Sahar Massachi rejoiced. Their parents were gone for the evening, so the children would spend a night out on the town eating hibachi, then in the warm , blanket-covered confines of their home watching two rented movies. One featuring a machine with the soul of a man, the other featuring a man encased in the shell of a machine.

“Iron Man is a scathing critique of American imperialism…a fascinating character study, a compelling Cold War critique, a subtle plea for liberal internationalism, and a defense of a series of theses presented to the world in America’s founding documents.”

“Iron Man, who represents an imperial America, can only win Pyrrhic victories. ”

Interested in the argument behind those quotes? I’ve been meaning to watch Iron Man ever since I read Spencer Ackerman’s brilliant essay, “Iron Man Versus the Imperialists”, back in May.

Iron Man represents the evolution of American psyche throughout the Vietnam era. Originally a straightforward symbol of American technological advances leading to military might, Iron Man was used as a straightforward thrasher of the Vietnamese. As doubt about the war mounted at home, his authors re-evaluated his persona. Iron Man, a symbol of the military-industrial complex, explored structural critiques of imperialism, the nihilism of hedonism, the dangers of mixing wide-eyed ideals with military adventure.

Iron Man is a superhero. Cold-War product or not, Marvel couldn’t very well turn him into a villain. Writers in the 1970s and 1980s solved the problem in two creative ways. First, the comic adopted the New Left’s structural critique of Vietnam — the war was the inevitable product of a systemic belief in unrestricted capitalism, American exceptionalism, and racism — by making Stark Industries an enemy of poor Tony Stark, who had unleashed malevolent forces he couldn’t control. Thus Iron Man’s nemesis became a black-mirror version of himself: the ruthless metal juggernaut (another metal-suit weapon) subtly named Iron Monger, controlled by rival defense-industry bloodsucker Obadiah Stane. More cleverly, Stark’s best friend Jim Rhodes became a second Iron Man — but one sent into a paranoid frenzy of destruction by the armor’s inability to interface properly with his brain. Rhodes’s secret identity? War Machine.

The second way Marvel subtly readjusted Iron Man for America’s post-Vietnam sensibilities was to reveal that the reason Stark could control neither his company nor his relationships was that he couldn’t control himself. Stark’s booze-soaked, womanizing lifestyle was cleverly reinterpreted as rampant alcoholism and self-loathing. His drive to save the world was nothing more than a martyr complex born of a callow solipsism. It was a brilliant maneuver by the writers. Iron Man began to ask America: Would you trust such unfettered, unaccountable power to someone this messed up? The introduction of War Machine took the critique a step further, showing that the very act of donning the armor makes you messed up. Some exercises of power are too dangerous to be left in the hands of one man. The writers never turned Iron Man into a villain — that would have been the easy way out. Instead they presented a fascinating character study, a compelling Cold War critique, a subtle plea for liberal internationalism, and a defense of a series of theses presented to the world in America’s founding documents. It helps that Iron Man also blows stuff up.

Really, read all of it. Then read about the Superman Approach to Foreign Policy.

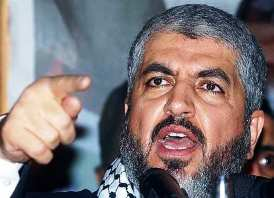

Is it just me, or does Iron Man villain Sayed Badreya resemble Hamas leader-in-exile Khaled Meshal?

That was funny. But if you know Arabic, I try to talk like Anwer Sadat of Egypt. My Hero.

Thx

Sayed Badreya